Set in December, with all the holiday trimmings in view, Cover Up is definitely a Christmas movie. Yet, its title clearly implies a noir universe where ulcerous secrets are smoothly skinned over by  patterns of social respectability. In the film, Dennis O’Keefe plays an insurance investigator sent to a small town at Christmas time to investigate whether the death of a policy holder was truly suicide. O’Keefe’s his repertoire of skeptical, somewhat hard bitten, though sometimes sympathetic noir protagonists (The Leopard Man, Raw Deal,T-Men, Walk a Crooked Mile), sets us up for a symbolic stripping away holiday cheer hiding dark secrets. patterns of social respectability. In the film, Dennis O’Keefe plays an insurance investigator sent to a small town at Christmas time to investigate whether the death of a policy holder was truly suicide. O’Keefe’s his repertoire of skeptical, somewhat hard bitten, though sometimes sympathetic noir protagonists (The Leopard Man, Raw Deal,T-Men, Walk a Crooked Mile), sets us up for a symbolic stripping away holiday cheer hiding dark secrets.

On the surface, the holiday season seems to characterize this small town as an embodiment the idyllic. Right off the bat, we’re immersed in Christmas cheer and fellowship, as the investigator helps a young woman, Anita Weatherby, returning to her family, so packed with presents that they burst from her arms and off the train. His Christmas good will in helping her is rewarded by her friendly, joking family inviting this helpful stranger to their On the surface, the holiday season seems to characterize this small town as an embodiment the idyllic. Right off the bat, we’re immersed in Christmas cheer and fellowship, as the investigator helps a young woman, Anita Weatherby, returning to her family, so packed with presents that they burst from her arms and off the train. His Christmas good will in helping her is rewarded by her friendly, joking family inviting this helpful stranger to their  house. He accepts their invitation to visit and share in the brightness, warmth, and humor of their home, filled with cheery Christmas decorations. Still, the family is not cloyingly saccharine, instead, kidding him and one another pointedly but good naturedly. In the same mood, Doro Merandes plays their housekeeper, Hilda, in Margaret-Hamilton-style – not as a Wicked Witch of the West but with salty comments delivered in perfect dead pan. That Mr. Weatherby, the pater familias, carries the authority of bank president seems to indicate that his warmth, tempered by dry humor, is the characteristic mode of the town. house. He accepts their invitation to visit and share in the brightness, warmth, and humor of their home, filled with cheery Christmas decorations. Still, the family is not cloyingly saccharine, instead, kidding him and one another pointedly but good naturedly. In the same mood, Doro Merandes plays their housekeeper, Hilda, in Margaret-Hamilton-style – not as a Wicked Witch of the West but with salty comments delivered in perfect dead pan. That Mr. Weatherby, the pater familias, carries the authority of bank president seems to indicate that his warmth, tempered by dry humor, is the characteristic mode of the town.

Investigator Sam sees this family as not just a haven of goodwill but a magnet drawing out the generosity and friendliness he keeps hidden beneath a protective layer of sharp cracks and skepticism. He shows up on the Weatherby doorstep, not merely planning to kibbitz and take out Anita on a date. He is thoughtful enough to bring a compact as an early Christmas present for the younger sister so she won’t feel slighted. He even impresses skeptical Hilda as an acceptable  addition to the family circle. His attraction to the Christmas warmth of companionship is decisively conveyed as he approaches the house in the dark shadows of late December cold, bowed against the wind, then straightens up and smiles on seeing Anita reading in the window, the lit Christmas tree in the background. In fact their friendly banter marks them as embarking on romantic adventure typical of 1940s comedy/romance. addition to the family circle. His attraction to the Christmas warmth of companionship is decisively conveyed as he approaches the house in the dark shadows of late December cold, bowed against the wind, then straightens up and smiles on seeing Anita reading in the window, the lit Christmas tree in the background. In fact their friendly banter marks them as embarking on romantic adventure typical of 1940s comedy/romance.

The imagery of the town itself abounds with Christmas warmth. As the bus carrying Anita and Sam into town from the train station arrives, a Santa Claus is merrily ringing a bell over a pot where he collects donations of holiday charity. The Weatherby house is bright with The imagery of the town itself abounds with Christmas warmth. As the bus carrying Anita and Sam into town from the train station arrives, a Santa Claus is merrily ringing a bell over a pot where he collects donations of holiday charity. The Weatherby house is bright with  daytime sunshine; at night electric lights, Christmas tree bulbs, and flickering hearth light create a comforting contrast to the dark December night. The rich, warming coats of fur and wool, as well as scarves and gloves, evoke a barrier against winter freezing. There’s even a lovely Christmas tradition of the whole town coming together in celebration when old Dr. Gerrow will light the enormous town Christmas tree and hand out presents to the children. Light against darkness. daytime sunshine; at night electric lights, Christmas tree bulbs, and flickering hearth light create a comforting contrast to the dark December night. The rich, warming coats of fur and wool, as well as scarves and gloves, evoke a barrier against winter freezing. There’s even a lovely Christmas tradition of the whole town coming together in celebration when old Dr. Gerrow will light the enormous town Christmas tree and hand out presents to the children. Light against darkness.

In this moment, though, we can see the corruption skinned over by good fellowship seeping through. The doctor, at first, is mysteriously absent, then is revealed to be dead, discovered in his out-of-town home by the sheriff. Significantly, this scene of camaraderie in solstice celebration ends  with the faces of disappointed children and the pine tree’s lights flickering against almost enveloping darkness. Furthermore, as light and warming as are the interiors of the Weatherby home, the night outside where Sam and Anita walk and romance is surrounded by dark shadows and implied cold. The mansion where Philips died also encompasses Anita and Sam, later Sam, Sheriff Best, and Mr. Weatherby, in shadows that distort, conceal, isolate, and threaten. In a with the faces of disappointed children and the pine tree’s lights flickering against almost enveloping darkness. Furthermore, as light and warming as are the interiors of the Weatherby home, the night outside where Sam and Anita walk and romance is surrounded by dark shadows and implied cold. The mansion where Philips died also encompasses Anita and Sam, later Sam, Sheriff Best, and Mr. Weatherby, in shadows that distort, conceal, isolate, and threaten. In a  telling scene, flickers of light in the darkness come to imply perfidy and corruption as the “lovable” maid Hilda resolutely undercuts Sam’s quest for the truth and order by burning a beaver coat that implicates Mr. Weatherby in Phillips’s murder. Interestingly, the coat no longer suggests protection from hostile nature but implicates the “upright” in crime. Now suicide is revealed to be murder, while the victim is, himself, revealed to be “a malignant growth strangling the town.” So, where does justice rest concerning this death? telling scene, flickers of light in the darkness come to imply perfidy and corruption as the “lovable” maid Hilda resolutely undercuts Sam’s quest for the truth and order by burning a beaver coat that implicates Mr. Weatherby in Phillips’s murder. Interestingly, the coat no longer suggests protection from hostile nature but implicates the “upright” in crime. Now suicide is revealed to be murder, while the victim is, himself, revealed to be “a malignant growth strangling the town.” So, where does justice rest concerning this death?

All the characters Sam faces in his investigation become almost impossible to pin down. The family that had seemed to offer him the warmth and stability he’d never had, he finds cannot be trusted, their dependability, at times even their morality, twisted and tangled by loyalties, fears, or ignorance. Mr. Weatherby, supposedly a paragon of the town and representative of its order, becomes a major suspect in the murder of Phillips.

Anita, the smart young woman whose wit and warmth had led Sam to see her as a beacon of hope  for belonging, betrays his trust in order to protect her father. In fact, the reflection of her in a mirror as she hides from Sam after obstructing justice to protect her father reverses the earlier image of her as the beacon guiding him to human relations. Here, rather than being before him, she lurks behind him as he stands uneasily sensing something is wrong, threatening. Though both images were linked to glass, where previously the clear panes revealed her as at peace and content, now she is both more distant, existing as only a reflection, and one step removed, hidden from him, the heavy door and the lines of the mise en scène reinforcing their isolation. for belonging, betrays his trust in order to protect her father. In fact, the reflection of her in a mirror as she hides from Sam after obstructing justice to protect her father reverses the earlier image of her as the beacon guiding him to human relations. Here, rather than being before him, she lurks behind him as he stands uneasily sensing something is wrong, threatening. Though both images were linked to glass, where previously the clear panes revealed her as at peace and content, now she is both more distant, existing as only a reflection, and one step removed, hidden from him, the heavy door and the lines of the mise en scène reinforcing their isolation.

The salty but lovable maid, who had seemed to welcome Sam into the family in her own reserved way, also lurks unobserved and one step removed in the mirror where she hears of Sam’s threat to her family. She also thwarts his search for truth to protect her clan when she unabashedly destroys evidence that would lead him to the truth and lies to his challenge, looking him dead in the eye. The salty but lovable maid, who had seemed to welcome Sam into the family in her own reserved way, also lurks unobserved and one step removed in the mirror where she hears of Sam’s threat to her family. She also thwarts his search for truth to protect her clan when she unabashedly destroys evidence that would lead him to the truth and lies to his challenge, looking him dead in the eye.

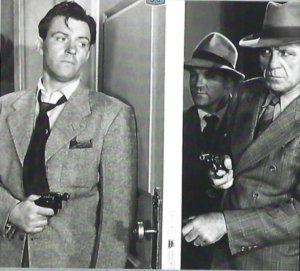

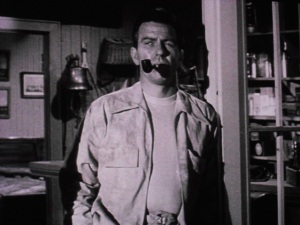

Maybe the most interesting of all is William Bendix’s Sheriff Best. Is the name ironic? The “best” at what, one wonders, watching him: Deception? Double-dealing? Murder, itself? How should an audience read the town’s master of law and order when with affable obduracy he insists on his suicide verdict despite all the evidence that Sam demonstrates add up to murder? Casting Bendix keeps audiences guessing by playing on the concept of the availability heuristic. For Bendix is as well-known in the noir universe as much for his lovable tough guys (The Web, Race Street, Detective Story) as for his vicious thugs (The Dark Corner, The Glass Key, The Big Steal).

These two medium closeups of Sheriff Best capture both incarnations of the Bendix noir personae.

Finally, Sheriff Best’s setting up subtle roadblocks to the investigator’s attempts to uncover the truth, as well as his tone of laid-back affability, just suggesting steely threat, then back to easy charm, heightens uncertainty over which noir Bendix holds the power of law controlling the town.

This image from the first meeting of sheriff and investigator, where they sit down to parry verdicts  back and forth brings this point home. They are seated on opposite sides of a desk, like opponents in a chess match. The Christmas presents between the two in the shot do not bond them in seasonal amity, but form a barrier between opposing forces – visually emphasizing a subversion of “Christmas fellowship” as much as the men’s amiable sounding but antagonistic verbal sparring and both refusing to face the other. A wreath above and between them, just out of shop, reinforces this point. Even more sinister, in the denouement, a tone of easy good will coats but does not hide the two men’s opposition. When Sam pleasantly checks Best by pointing out that neither has ascendancy because both carry concealed guns, Best chillingly checkmates him with the easy and reasonable delivery of his assertion that if Sam shoots him it’s killing “a law man,” but “If I [the sheriff] get you with my gun . . .it’s just a lot of votes in the next election.” back and forth brings this point home. They are seated on opposite sides of a desk, like opponents in a chess match. The Christmas presents between the two in the shot do not bond them in seasonal amity, but form a barrier between opposing forces – visually emphasizing a subversion of “Christmas fellowship” as much as the men’s amiable sounding but antagonistic verbal sparring and both refusing to face the other. A wreath above and between them, just out of shop, reinforces this point. Even more sinister, in the denouement, a tone of easy good will coats but does not hide the two men’s opposition. When Sam pleasantly checks Best by pointing out that neither has ascendancy because both carry concealed guns, Best chillingly checkmates him with the easy and reasonable delivery of his assertion that if Sam shoots him it’s killing “a law man,” but “If I [the sheriff] get you with my gun . . .it’s just a lot of votes in the next election.”

Dennis O’Keefe’s place in the noir universe as hard-bitten outsider trying to belong without sacrificing integrity makes him an apt proxy for the audience looking for order and stability in an uncertain and corrupt world. His character’s confrontation with Bendix’s sheriff in the shadows of the murder mansion where he’d planned to lure the murderer into a trap creates a disconcerting, even haunting Dennis O’Keefe’s place in the noir universe as hard-bitten outsider trying to belong without sacrificing integrity makes him an apt proxy for the audience looking for order and stability in an uncertain and corrupt world. His character’s confrontation with Bendix’s sheriff in the shadows of the murder mansion where he’d planned to lure the murderer into a trap creates a disconcerting, even haunting  embodiment of the danger of noir uncertainty. All on Christmas Eve. Interestingly, when the sheriff first enters, the visuals throw us off balance by placing Best more in the light and shadowing Sam, the seeker of truth, in a threatening, sneaky pose in the shadows. Which of the two antagonists can we trust? Is Sam literally and figuratively in the dark? Is he bringing darkness into the Christmas world or revealing what was there all along? This use of shadows enveloping the men as the scene progresses creates a space of confusion and doubt that mirrors the uncertainty of reality as Sam raises suspicions and presses for honest answers, and the sheriff seeks to control that truth for unclear ends, gradually unveiling indirectly what may or not be honest. embodiment of the danger of noir uncertainty. All on Christmas Eve. Interestingly, when the sheriff first enters, the visuals throw us off balance by placing Best more in the light and shadowing Sam, the seeker of truth, in a threatening, sneaky pose in the shadows. Which of the two antagonists can we trust? Is Sam literally and figuratively in the dark? Is he bringing darkness into the Christmas world or revealing what was there all along? This use of shadows enveloping the men as the scene progresses creates a space of confusion and doubt that mirrors the uncertainty of reality as Sam raises suspicions and presses for honest answers, and the sheriff seeks to control that truth for unclear ends, gradually unveiling indirectly what may or not be honest.

How does the film end? Well, that would be telling. I wouldn’t want to spoil it for you. Let’s just say that things are not always as they seem, that the film looks for wiggle room in what the law demands and what is fair, in what you can expect of human beings. “Merry Christmas” was never such an ironic closing to a movie – I think!

|